It may be a massive cannibalization of industry, but there appears to be a case for public insurance. This became clear to me when I ran some simple numbers.

My insurance agent showed me a plan where a term policy with a $1M sum assured would cost over $200 per month. I thought it was outrageous (i.e.: working on an inflated probability of death), so I went home and did some estimates. (Point of separate note: NTUC income has a term policy with a $1M sum assured for 20yr for $60 per month given 30 was one's last birthday.)

SPF statistics reported about 285 fatal/serious accidents annually for 2006 and 2007 when

Singapore's population was about 4.5M. This gives an estimate a lower bound for the rate of death and serious accidents for all causes each day (1.73 x 10

-7). Let's suppose, to be conservative, that an upper bound for the true rate is 3 times that since reputedly road accidents are a "leading cause of death, et. al.".

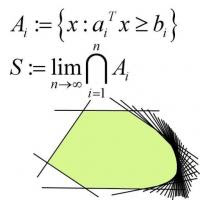

Here is a simple model for insurance. Each day an insured party pays a day's premium, if he/she encounters an unfortunate event (with the above probability), a payout is made and premium payments stop. If nothing happens by a terminal age of the insurance policy (I used 40 years), no further premiums are paid and no payouts are made (dealings with the insurer end).

Going into some technicalities (skip the paragraph to get to the conclusion), the geometric distribution was (obviously) used as a basis for the computation of the expected income of the agency. The answer comes is three parts: (a) premiums paid given an incident, (b) incident payout given an incident, (c) premiums paid given no incident. An annoying thing happened to me when I was calculating this. I was evaluating an expression (I think it was (a)) which was the derivative of some expression that I knew to be increasing. It wasn't, at least until I realized that Excel's LOG function is base 10. (One performing this computation with some "numerical sense", will know why I bring in the LOG function.)

In any event, it turns out that my insurer uses at least 91% of the premiums to cover overheads such as commissions. NTUC uses at least 73%, noting the lower premium. This is before factoring in the higher premiums at later ages. This is high.

Given a buffer that can be tapped into and repaid slowly with low interest, an insurer can insure 4M citizens for 70 years from birth with a $1M sum assured, working with $352M annually for administration and accumulating $89M on average each year for a $25 monthly premium. The buffer is there to handle variance in payouts between years. One would expect about $761M in payouts each year, and assume that 99% of the time payouts are less than $1.52B, within 9 years one would accumulate enough to buffer against a $1.52B payout year without tapping the buffer. Within 20 years, the scheme would probably never have to touch the buffer. Once a sufficiently large reserve is accumulated, surpluses could then start going into a foundation to provide opportunities for the under privileged or some other worthy cause.

$352M administration for 2M citizens may be low. But this works if business expenses are kept low. Especially marketing and sales. Also, the buffer may be operationally realized, initially, by government debt via the bond market. Debt can be rolled over the same way most governments and companies do. The national reserves do not have to be touched at all.

As a start such a scheme might just handle only accidental death and Total Permanent Disability (TPD) up to age 70 (at which age it might be assumed that the formerly insured would have been able to provide for his/her dependents). This would ensure that the low administration cost would be easily achieved. Perhaps even more rainy day reserves could be accumulated if the costs turn out to be lower.

There are issues to be worked out. Such as costs for dealing with insurance fraud. Incentives for fraud can be handled by dynamically adjusting the sum assured to annual income based on the last tax assessment (and charging premiums accordingly), and perhaps with a tapering of payouts as age 70 approaches. Payouts could be made gradually to lessen the effects of variance. However, these are problems in incentives and operations that can be worked out.

This is heavy duty security for our citizens. Who cares if we drive the death and TPD wings of insurance agencies out of business. They weren't using much of our money to protect us anyway.

If this goes through, a national healthcare system might be possible. I apologize to the L-

p norm loving people (for small

p), but I take a "uniform convergence" (L-

infinity) view of approach to a first world nation. Rather than just increasing the total welfare, we have to make sure that the least well off are lifted up.

This should be an element of our national strategy --

the elimination of accidental poverty. Notably, this does not entail transfer of wealth from the rich to poor. It is just a matter of good management and economies of scale.

Singapore has already disadvantaged singles as a side effect of part of its national strategy. My sense is the government has been too friendly with big business to the detriment of many of its citizens (i.e.: when interests are not weighted by income). Why should

part of the insurance industry be sacrosanct?