To cut a long story short, based on their observed actions, teacher KPIs appear to be based on a test score metric. Management often only sees numbers and assumes that all is well. However, proxy metrics are only proxies, and in extreme situations they may lose their association with the value they purport to represent.

No matter what people claim about the public-spirited virtue of educators, they are human — intelligent ones at that — and respond very keenly and creatively to incentives. The pursuit of rankings and test scores is a natural response to KPIs being set in that direction. The unintended fallout are, unfortunately, the well-established phenomena of forcing students to drop subjects they are less than excellent at, the trivialization of non-classroom activities and the subordination of such activities to those of a more test-relevant nature. It was almost as if educators were told: "This is the syllabus; and this is the rewards and remuneration structure. Now get to work." I understand these statements are blunt and unrefined, but they capture the gist of the situation.

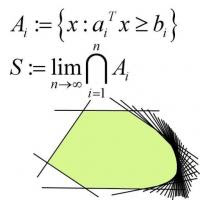

While test scores and other KPI aligned measures have improved greatly, it is a fact that unintended consequences have cropped in due to the process of chasing incentives — a naturally arising optimization process. Here "optimization" is the process of making decisions so as to maximize some measure of performance and or minimize some measure of undesirability subject to certain constraints. As a practitioner of quantitative optimization techniques, I would like to state that optimization is an unintelligent process that has to be guided by an intelligent user. An example from the distant realm of finance may shed more light on the situation. When practiced naively, portfolio optimization performs poorly. This is because, incompletions in the data used to guide the process are maximally exploited. This results in a proposed portfolio that would have performed well in hindsight, but severely under estimates future risk. (The pure naive form is beautiful theoretically but needs to be embellished before it is roadworthy.)

Sociologists have proposed that when dealing in the "economic realm" (with rewards and remuneration, for instance), individuals have a tendency to make cold rational decisions. Analogous to the unintended consequences of our education system, the example from finance shows how omissions are exploited in a raw unfeeling optimization process.

Unintended consequences creep in to any well meaning statement of value. For instance, as much as I love the sentiment behind rewarding the hardworking, the execution of such a policy is literally fraught with (economic) peril. Effort should not be rewarded as much as results, as it gives students an incentive to put on a show instead of directing their efforts at improvement. I believe the well established term is "wayang". Promoting a culture of "wayang" would be counterproductive and harmful to our economy. We cannot give up the desire for a culture of performance, but it is important that the pursuit of a proxy to the abstract notion of "performance" does not retard the achievement of less quantifiable true goal. Scores alone are a poor measure of effectiveness; I'd like to suggest something a little more nuanced.

I'd like to propose using a type of metric that balances various factors such as (student) appraisal (as a proxy to "students feeling they got something out of the class"), captures the tradeoffs involved in working to achieve the various ends of education and promotes the centering of the actions of teachers to give students a more well rounded experience (which some theories of education tout as superior).

In the graphic below, effectiveness has been presented in the form of indifference curves. "Higher curves" indicate greater effectiveness. The green dotted lines indicate that for the "focused" teacher to progress in the assessment scale, there are minimal achievements in each attribute for each assessment level. This combats lopsidedness. The asymmetry in the minimal-effectiveness-for-progression boundaries captures the fact that we are a performance culture, and that must be foremost in the minds of teachers. In this manner, evaluation-optimizing teachers may straddle the green lines, but the evaluation structure limits the damage of their optimization. (In the diagram, only a (10,10) achieves effectiveness level 10, the true master teacher.)

Such a metric may be extended to multiple criteria. The curves here are of the form:

(Effectiveness)2 = (Metric 1) x (Metric 2),

the natural generalization would be

(Effectiveness)n = (Metric 1) x (Metric 2) x ... x (Metric n).

Another practice in optimization has been to constrain solutions to take a particular form; at times to preclude undesirable behavior and at times with the explicit aim of making them robust to the slings and arrows of outrageous fortune. On the latter, it seems that "robustness" to the onslaughts of the real world is well correlated to "experience".

Less quantitatively, I'd also like to mention that there should be requirements for the education process that ensure that students have had a prior "experience set", leaving the system, as evidence of exposure to certain situations. This would increase the likelihood of a "robust response" to changing situations on the part of students. This would of course represent additional teaching workload and the question arises of the marginal benefit of this and whether it should displace something else. This is very much in line with the "Desired Outcomes of Education" expressed by MOE. This is considerably harder to design well.

Set up a well thought-out optimization problem, and make sure your solutions are robust.

No comments:

Post a Comment